Expo 2025 Osaka: Encircling a Divided World

Japan Pavilion

As Expo 2025 Osaka draws to a close, its constellation of national pavilions reveals a world of contrasts and a subtler narrative: how architecture becomes diplomacy, soft power and an expression of identity in timber, steel and light

World Expos have always balanced diplomacy and national prestige. Osaka’s edition gathered close to 160 countries — around 80 per cent of the world — an extraordinary act of participation driven as much by diplomacy as design. For many Asia Pacific nations, saying yes was an act of goodwill toward Japan, not necessarily a matter of economic return.

Architect Sou Fujimoto, who designed Expo 2025’s signature structure — the vast Grand Ring — explains that he sees the event as a rare antidote to fragmentation: ‘The meaning of the Expo itself is getting more and more important. Because of the current global situation, everything is divided — the meaning of Expo is to reunite the whole world. This time almost 80 per cent of the world is joining. That is a strong counter-message, that people from so many different backgrounds and cultures can come together to create our future.’

His Grand Ring — a two-kilometre-long timber arcade of glulam beams rising 20 metres — embodies that ideal physically: an open halo of Japanese cedar and cypress combined with Scots pine encircling the Expo grounds, uniting everything within. Yet this idealism sat alongside logistical and financial reality.

Image by Erik Augustin Palm

Image by Erik Augustin Palm

Osaka’s organisers actively courted friendly nations to ensure strong participation, while local contractors, facing soaring costs and thin margins, hesitated to take on Expo projects. Japan’s severe labour shortage was a factor in several smaller countries downsizing or delaying their pavilions. Delivering hundreds of buildings on time became a feat of project management — and a test of diplomatic patience. Still, even amid these constraints, the Expo became a laboratory of cultural expression. Some pavilions turned compromise into creativity; others settled for spectacle. Together, they reveal much about how nations see themselves — and how they wish to be seen. An Expo pavilion is a national manifesto in built form. Some governments treated it as a serious act of design, others as little more than branding.

Australia’s pavilion, by global firm Buchan, falls somewhere in between. Shaped like a giant eucalyptus gumnut bursting into bloom, it glows in pinks and oranges on Osaka’s artificial island. ‘The pavilion’s overarching theme, ‘chasing the sun’, is expressed through both its form and its journey,’ says Buchan associate and project creative lead Dong Uong. ‘The shell’s dynamic curvature and vivid colours evoke a gumnut bursting into flower — a metaphor for growth, energy and a future full of promise. Within, the exhibition invites visitors on a sensory bushwalk following the sun across land, sky and sea Country, guided by songlines that carry deep cultural knowledge across generations.’

The result is exuberant and photogenic — part immersive theatre, part tourism campaign. Critics back home, though, have questioned whether the investment has advanced Australian architecture in any meaningful way. Pavilion representatives have countered that simply delivering such a complex build on schedule was a triumph of collaboration across cultures. The question that lingers: does project fulfilment equal legacy?

Australia Pavilion

Australia Pavilion

Australia Pavilion

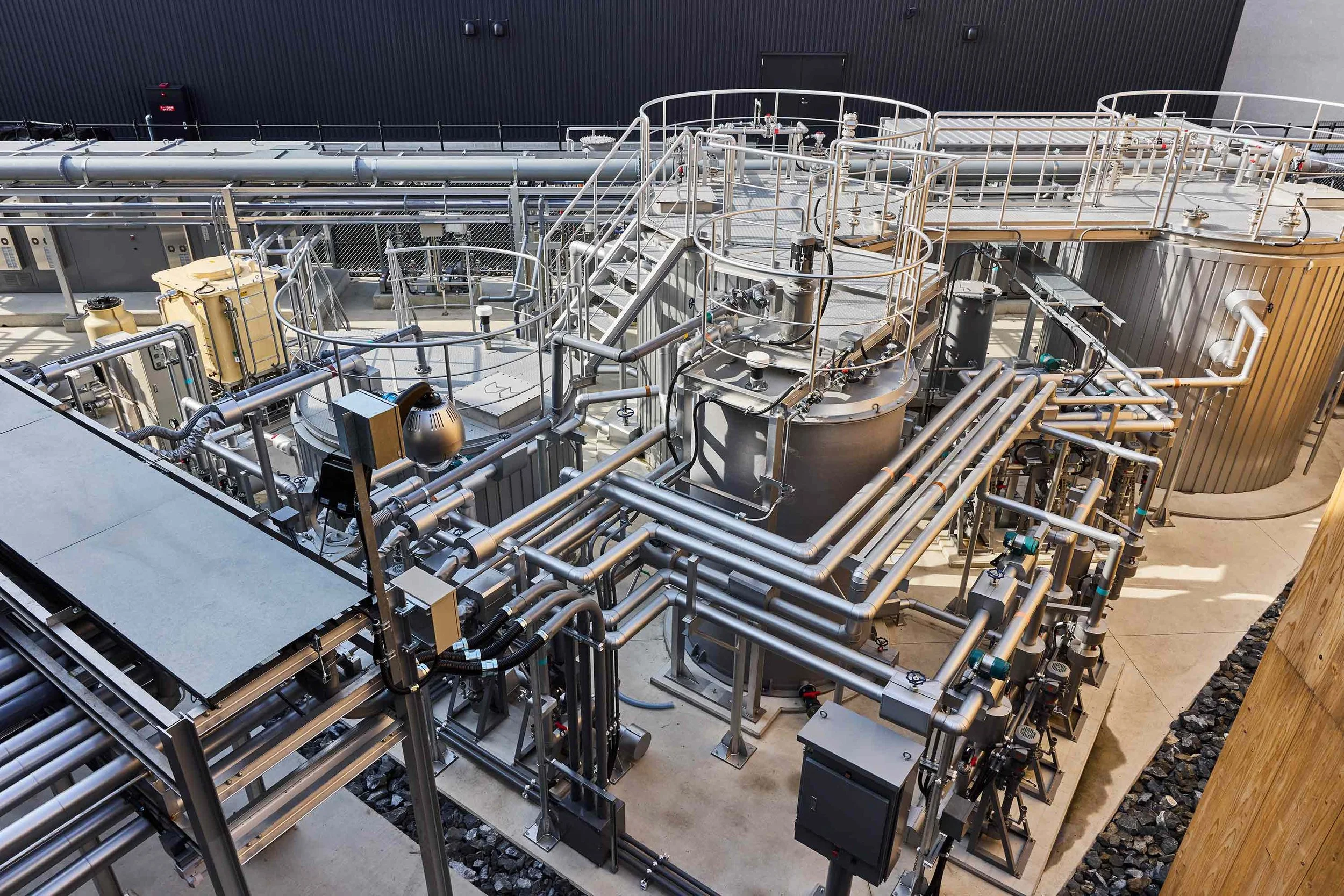

Japan’s own pavilion, by Nikken Sekkei with creative direction by Oki Sato of Nendo, offers the antithesis of spectacle. Its theme, ‘between lives’, explores the cycles connecting humanity and nature through a looping plan of cross-laminated timber panels. ‘The Japan pavilion’s theme expresses the circulation of life and our connection to nature through both architecture and exhibition,’ explains Japan pavilion counsellor Teruyuki Shirakawa. ‘Visitors can recognise themselves as part of this greater cycle and consider what they can do for a sustainable society.’ Inside, the use of algae, microorganisms and recycled biowaste illustrate Japan’s deep-rooted reverence for impermanence and renewal. Rather than selling an image, it cultivates a mindset — quietly powerful, distinctly Japanese.

Japan Pavilion

Japan Pavilion

Japan Pavilion

Japan Pavilion

Nearby, five nations share one roof — including this writer’s birth nation, Sweden. The Nordic pavilion — or, Nordic Circle — designed by Italian architect Michele De Lucchi and AMDL Circle with exhibition content by Kvorning Design, among others, is an essay in humility. From the outside it resembles a barn — familiar, warm, unpretentious — but within it radiates collective purpose. ‘The pavilion draws inspiration from traditional Nordic building forms such as barns and Viking longhouses, which embody simplicity, functionality and harmony with nature,’ says lead architect Davide Angeli. ‘Its immediately recognisable shape reflects shared values of openness and community, a place where people and ideas can gather.’ Built entirely of Japanese cedar (sugi), the structure was designed for reuse. ‘Sugi was chosen as a conscious gesture of respect towards the host country,’ Angeli adds. ‘Collaborating with Japanese craftspeople allowed us to merge Nordic and Japanese traditions, both of which value wood as a living, expressive material.’

That mutual respect runs through the exhibition, where Kvorning created an enveloping sensory environment of Nordic self-idealisation: ‘The exhibition concept with the big “whirl” and the surrounding “landscapes” presents the Nordic region by triggering all senses,’ says Arne Kvorning. ‘Specially composed music describes our four seasons, and an immersive video show is projected on 700 sheets of handmade Japanese paper. All focused on well-being, democracy and openness.’ The pavilion can be dismantled like a well-crafted kit and reassembled back home — a literal model of circular economy thinking. Amid the Osaka Expo’s visual noise, the Nordic Circle’s calming presence feels almost radical.

Nordic Pavilion. Image by William Mulvihill

Nordic Pavilion. Image by William Mulvihill

Nordic Pavilion. Image by William Mulvihill

Nordic Pavilion. Image by William Mulvihill

Not all pavilions whisper. A short walk away, the United Arab Emirates Pavilion rises as a forest of palm columns — a sculptural narrative of growth in arid lands. Inside, immersive soundscapes and cinematic projections dramatise Emirati resilience and opulence. It’s architecture as story and selfie backdrop, calibrated for emotional impact.

Then there’s Null2, a host nation signature pavilion by Tokyo- and Taipei-based Noiz Architects. The mirrored cube shimmers in the sea breeze; its metallic fabric skin ripples, fracturing reflections of sky and water into a digital haze. The name combines the programming term for ‘empty value’ with the Buddhist notion of kū — emptiness. The building itself becomes an interface, reacting to visitors’ movements and Osaka’s weather, dissolving boundaries between real and virtual. It’s equal parts artwork and architecture — and a reminder that in an age of screens, even a physical fair can meditate on the immaterial.

If the 2025 Osaka Expo’s architecture will be remembered for anything, it’s wood, wood — and wood. The Expo marks a global pivot toward timber as both aesthetic and ethic. ‘This Expo is symbolising a drastic change,’ says Fujimoto. ‘So many national and corporate pavilions are introducing wooden structures, bamboo and natural materials. It’s a message to the world that we are on the edge of a changing moment.’

The Grand Ring alone used around 27,000 cubic metres of timber — 70 per cent Japanese cedar and cypress, 30 per cent imported pine. ‘The wooden structure is a very strong strategy for sustainability,’ Fujimoto explains. ‘It works together with the cycle of the forest — we should create a cycle of nature and a cycle of our society. Building such a large structure in wood can be a model showing that even huge urban constructions are possible with timber.’

After the Expo, much of that material will be dismantled and reused for public projects across Japan. The Nordic pavilion is designed for disassembly and reuse — potentially even reassembled in Scandinavia. Australia’s steel sub-frame, borrowed from the Tokyo Olympics, was conceived for reuse and is expected to re-enter circulation. Even the Japan pavilion’s CLT panels are tagged for redistribution nationwide. For an event historically notorious for waste, these second lives feel momentous. Yet, how sustainable is the process of assembling and disassembling it all, in comparison?

Osaka’s achievement came at a cost. An overstretched construction sector, rising material prices, and immovable deadlines led to late-night builds and last-minute simplifications. During my visits in April and mid-summer, parts of the Grand Ring remained closed for adjustments, and a few pavilions hadn’t yet opened their full interiors. Yet such imperfections are almost a World’s fair tradition — ephemeral cities built in haste and dismantled in hope. When the lights dim and the crowds disperse, most of Yumeshima’s timber and steel will be packed away. What remains is symbolic: a memorial fragment of the Grand Ring and a global experiment in design diplomacy.

For governments, Expo 2025 was a stage for soft power; for architects, a crucible of innovation under pressure; for visitors, a day trip around the world. The success of its architecture cannot be measured in permanence but in the questions it leaves behind: how can nations practice sustainability not only in rhetoric but in construction? How can design bridge local craft and global message? And in an age of virtual everything, why do we still gather under one roof?

The answers flickered each night along the Expo’s central avenue. On one side, Null2 shimmered — a mirror of digital life. On the other, the Nordic barn glowed softly from within. High above, Fujimoto’s colossal wooden halo framed it all, alive with people from every continent strolling its curve. From this particular vantage point, his vision of unity becomes real: architecture truly as a commons.

When it’s gone, fragments of timber will travel the world, but the gesture will endure — proof that design, at its best, can build bridges even as it disappears.

Text by Erik Augustin Palm